Barter Economics – Then and Now

Barter economics is nothing new.

It thrived during the Middle Ages, was a lifeline during the Great Depression, and in 2020, saw the light of day again during the Covid pandemic.

Around the world, people turned to swapping, trading and bartering, whether to do their bit for the local community, save money or simply source hard-to-find baking ingredients. A bit of fun.

However, during the past two years, with economic uncertainty looming and anxiety levels soaring, barter is fast becoming an emerging alternative solution to getting by… and may be the only way of survival should we run out of food, fuel, or unlimited water supply.

Or if banks run out of money.

Bank crises and the rise of the bartering

Some economists and historians have argued that the bank crisis caused the Great Depression. But others have looked at fundamental economic factors and regional histories and argued that banks failed due to the economic collapse.

Whether the fear of bank failures caused the Depression or the Depression caused banks to fail, the result was the same for people who had their life savings in the banks – they lost their money. At the beginning of the 30s, there was no deposit insurance. If a bank fails, you lose the money you had in the bank.

Because they struggled during the Great Depression.

Through the decade of the 30s, 9,000 banks failed. And when people started hearing of banks failing and closing, they wanted to take their money out before that happened to their bank. So with everyone doing that, the bank already has fewer funds from loaning out, and nobody spent money. So the banks were like, “sorry, we have no money to give you.”

- Between 1929 and 1932, the average American's income dropped 40 percent to about $1,500 per year.

- Milk cost 14 cents a quart, eggs were a nickel a dozen, and bread cost 9 cents a loaf.

- During this decade, 86,000 businesses failed, and 9,000 banks went out of business.

- In 1933 one-third of the U.S. working population was unemployed.

- By 1932, farm prices were about 65 percent of what they were about 20 years earlier.

Burning corn for fuel

In the first years of the Great Depression, the drought hadn't started yet. Rain was still falling, and crops were still growing. But, so many people were out of work that the market for food and other agricultural products dried up – well before the fields.

In 1925, corn sold at $1.07 per bushel. By November and December 1932, corn was selling for only 13 cents per bushel. Back then, most homes were heated, and food was cooked with coal. But by 1932, corn was cheaper than coal. So, farmers began burning their harvest rather than selling it.

If you talk with people who lived during the Depression repeatedly, you'll hear something like, “We were poor, but so was everyone else. We were all in the same boat.”

And, “we went to the store, but we didn't buy things. We traded.”

Trading corn for doctor’s services

During the Depression, the agricultural economy got so bad that many farmers were forced to trade their crops and other goods to people in town that they owed.

People bartered, trading goods and services directly with each other rather than going through the intermediate step of converting the goods and services into a cash value.

For example, a blacksmith shop would accept payment in the form of potatoes.

Or, a doctor would be paid with corn worth 10 cents a bushel. The doctor could hold on to it until the price rose to 50 cents a bushel – making a profit!

Barter is a natural solution.

Bartering is a cashless exchange system where two parties trade goods or services directly without money entering the conversation. In recent years, barter has enjoyed a resurgence to counter economic insecurity, unemployment, and worker exploitation.

For bartering to work, there needs to be a ‘double coincidence of wants. This means that both parties need to have what the other wants.

For example: Suppose Mr. Y wants a pair of shoes and has 5 kg of wheat to offer as consideration. In that case, he has to look for a person who wants 5 kg of wheat and has a pair of shoes to offer in return.

Characteristics of the barter system

Mutual Benefit: In the olden days, when society was not so developed and money was not invented. The barter system acted as a classical arrangement through which people could get what they needed by offering them some other commodity. In this way, the barter system mutually benefits the participants.

Reciprocal: In a barter system, the exchange is reciprocal, which means it is negotiated, wherein the participant gets the commodity they need in place of the commodity they are offering.

Absence of Money: In this trade, no money is involved in the transaction. The barter system existed when the economy was cashless, and there was no substitute mode for payment.

Informal Presence: At present barter system only exists in an informal manner and not as an official exchange method.

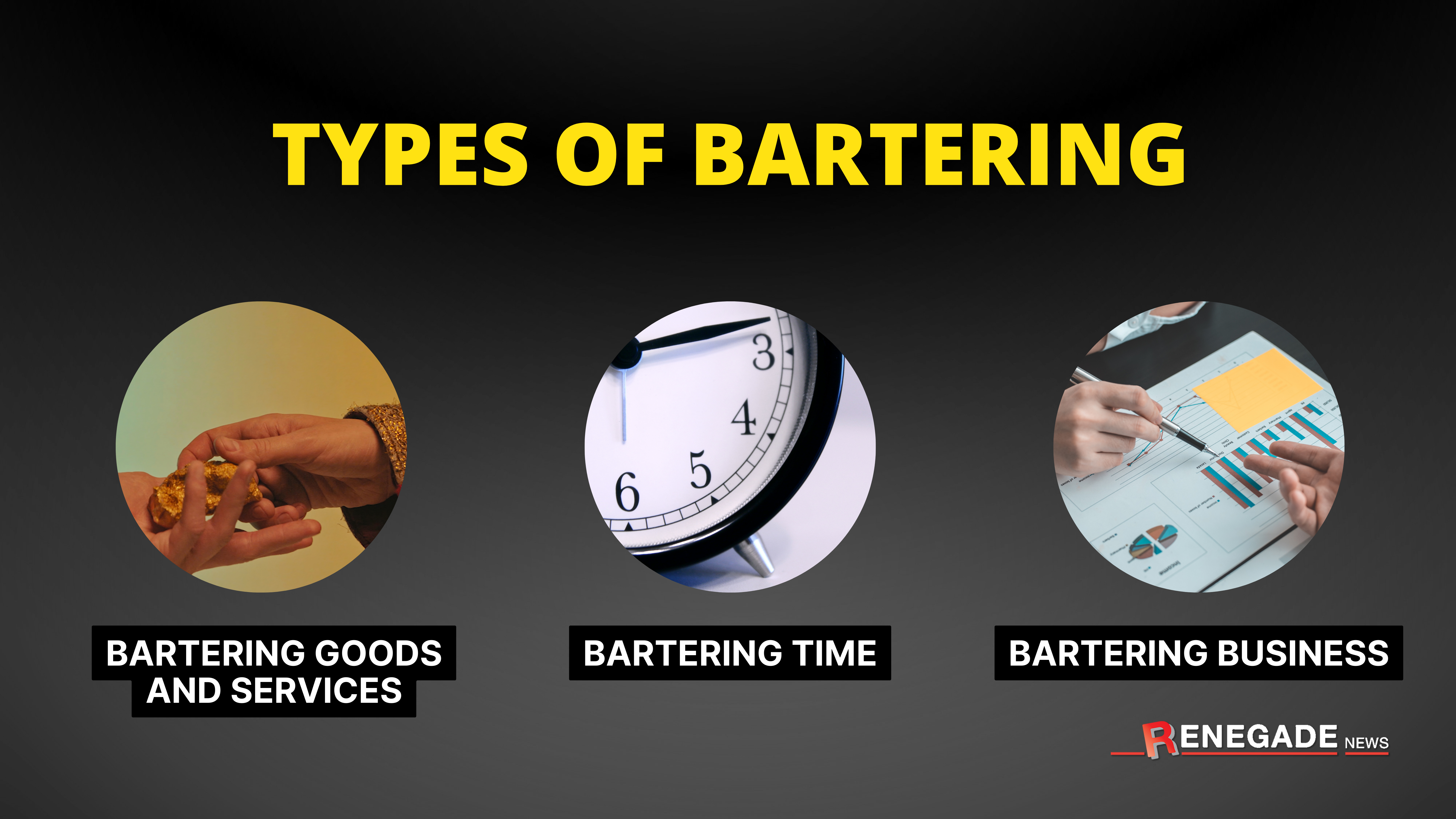

Types of bartering:

Bartering goods and services

The barter system is a system of exchange that was prevalent in the world centuries ago, before the introduction of the monetary system. In this arrangement, goods and services are traded for goods and services. This means that the parties exchange each other’s commodities directly without any mediation of money based on equivalent estimates of price and goods.

Bartering time

‘Time banking,’ which started in Japan in the 1970s and in the US in 1992, is seeing a jump in popularity. Members of a time bank spend one hour helping another member and can receive one hour of help in return. People offer and receive piano lessons, painting services, or language teaching.

Bartering business

Bartering isn’t just for individuals looking for baking items or help with grocery shopping, however. In ‘barter exchanges’ for business, participating organizations try to increase their yearly business by 10% to 15% by swapping their services for the services of other businesses.

Members can exchange their professional services for barter credit, which they can then use to ‘buy’ the services of another member. Most times, it is not a one-on-one trade. For instance, a landscaper would do a $5,000 landscaping job for a local dentist’s office. That does not mean he has to trade his labor for $5,000 of dental work; rather, he has an account at a barter exchange, which is credited 5,000 trade dollars, and he can spend that amount on any of the hundreds or thousands of members in that exchange.

Conclusion

Traders need to be patient. Bartering takes more time than buying with cash. Since bartering is so personal, it's important that traders not have a ‘win-at-all-costs’ attitude. While it's better to have relatively equal swaps, the most important thing is that all parties are satisfied with the result.