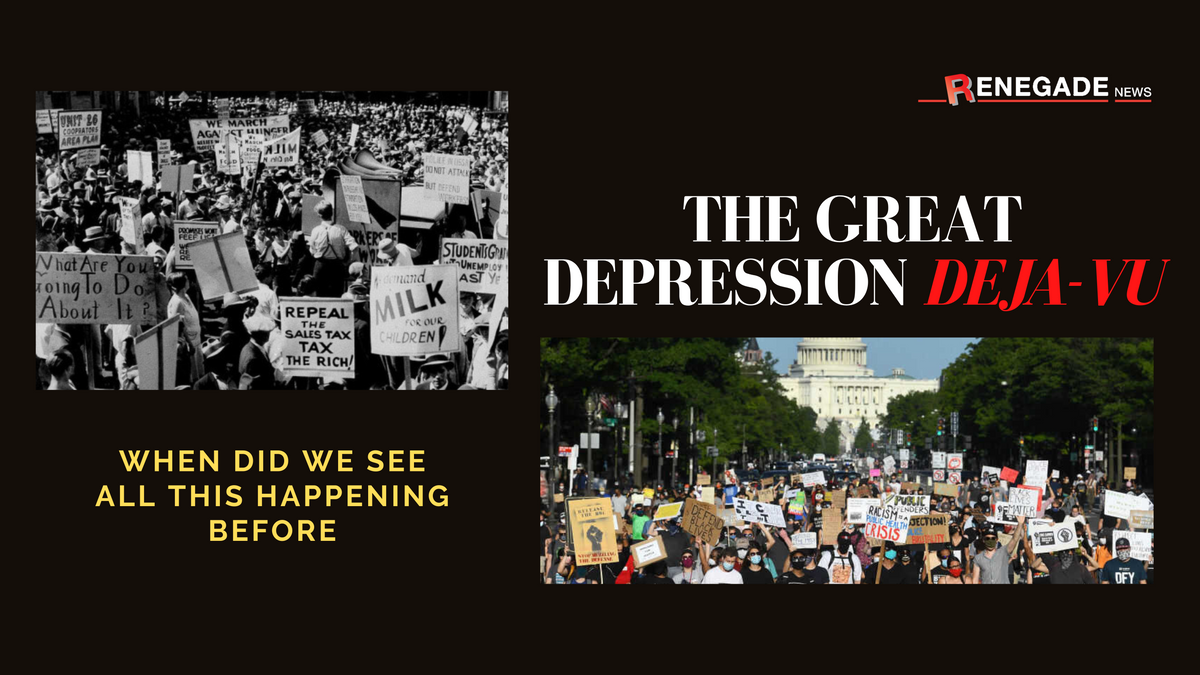

The Great Depression Deja-Vu: When Did We See All This Happening Before

In late October 1929 – just a few days before Halloween – investors in New York City began to panic. Stocks that they had bought at high prices started to drop. More and more investors sold their stocks at whatever price they could get. Over two days, the value of companies being traded on the stock exchange fell almost 13 percent on Monday and another 12 percent the next day. That day became known as “Black Tuesday.” Fortunes were wiped out. The stock market had crashed.

All across the US – and all around the world – people paid attention to the news closely. Some investors killed themselves. Millions of people from all over the world who owned stocks waited helplessly as stock values crashed.

After the crash and the Depression, land values dropped to less than half of what they had been. Their farm was no longer worth what they still owed on the land.

The stock market downturn continued for at least three years. By the time it was over, the average value of companies in the Dow Jones Industrials Average had dropped almost 90 percent – from a high of 381 to a low of 41. In other words, companies were worth barely more than 10 percent of their former value.

Jobs were hard to find.

Farmers and rural residents felt the stock market crash as well – people and companies that used to buy food and other agricultural products no longer had the money to buy much of anything. The crash and other factors produced an economic slowdown that lasted over 10 years and became known as “the Great Depression.”

Since the 1930s, there have been several stock market crashes and periods of economic slowdown. But there has never been another “Great” Depression.

Worldwide Depression

The depression that began in the United States in 1929 went around the world in the following years. By 1932, more than 30 million people could not find a job. That same year, industrial production worldwide was 38 percent less than in 1929.

As in the U.S., unemployment rates in Germany and Great Britain reached 25 percent in 1932. In Germany that meant that over 5.5 million people were out of work. Some historians point to that fact as one of the reasons that democracy broke down and Adolph Hitler gained dictatorial power.

What caused the Great Depression to become a worldwide event? Some economists say that the fact that there was an international monetary system tied to the price of gold made the different economies closely related. Problems in one large economy were passed on to others and eventually back to the country where the problems began.

Then came the bank failures…

As the economic depression deepened in the early 30s, and farmers had less money to spend in town, banks began to fail at alarming rates. During the 20s, there was an average of 70 banks failing each year nationally. After the crash during the first 10 months of 1930, 744 banks failed – 10 times as many. In all, 9,000 banks failed during the decade of the 30s. It's estimated that 4,000 banks failed during the year 1933 alone. By 1933, depositors saw $140 billion disappear through bank failures.

When a new president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933, banks in all 48 states had either closed or had placed restrictions on how much money depositors could withdraw. FDR's first act as President was to declare a national “bank holiday” – closing the banks for a three-day cooling-off period. The most memorable line from the President's speech was directed at the bank crisis – “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Foreclosures

Foreclosure is the legal process that banks use to get back some of the money they loaned when a borrower can't repay the loan. During the 30s, there were thousands of foreclosures.

The word “foreclosure” itself became a rallying cry for political movements.

Here's what often happens. During the 20s, many farmers borrowed money from banks to buy more land or new machinery. Farmers pledged their assets as security on loan. So if a farmer couldn't make the payments on a loan for land, the bank could take back the asset – the land – and sell it to get back their money.

In the 1920s, many loans were written when land values and crop prices were high. After the stock market crash, few people had the money to buy land, so land values plummeted.

Penny Auctions

As the pace of foreclosure auctions increased between 1930 and 1932, more and more farmers became desperate. Activists demanded that state legislators halt foreclosure sales. Angry farmers marched on the capitol buildings in several states, including Nebraska, where farmers took matters into their own hands.

In 1931, about 150 farmers showed up at a foreclosure auction at the Von Bonn family farm. The bank was selling the land and equipment because the family couldn't repay a loan. The bank expected to make hundreds, if not thousands of dollars.

As those who were there remember it, the auctioneer began with a piece of equipment. The first bid was 5 cents. When someone else tried to raise that bid, he was requested not to do so – forcibly. Item after item got only one or two bids. All were ridiculously low. The proceeds for that first “Penny Auction” were $5.35, which the bank was supposed to accept to pay off the loan.

The idea caught on. Farmers showed up as a group at auctions across the Midwest and physically prevented any real bidders from placing bids. But the banks figured out ways to get around these illegal Penny Auctions.

Eventually, several Midwestern states enacted moratoriums on farm foreclosures. Generally, the moratoriums lasted a year. The theory was that the Depression couldn't last that much longer, and then farmers would have the income to make their payments. But the Depression continued, the moratoriums ran out, and farmers lost their farms.

Radical Farm Protests

After four years of economic depression, farmers across the country were looking for new and sometimes radical solutions to their problems. As early as 1932, some farmers were trying to raise agricultural prices by physically keeping produce off of the market. The theory was that if farmers could reduce the supply, demand would rise, and prices would respond.

It didn’t work, and frustration continued to mount, leading to more violence and vigilantism.

Ninety years later, we are seeing a close replica in Post Pandemic America, specifically among landowners and farmers worldwide.

What is next? What should we be prepared for? And how will it affect us?

For more answers to the 2022/23 Great Repression, follow our YouTube channel